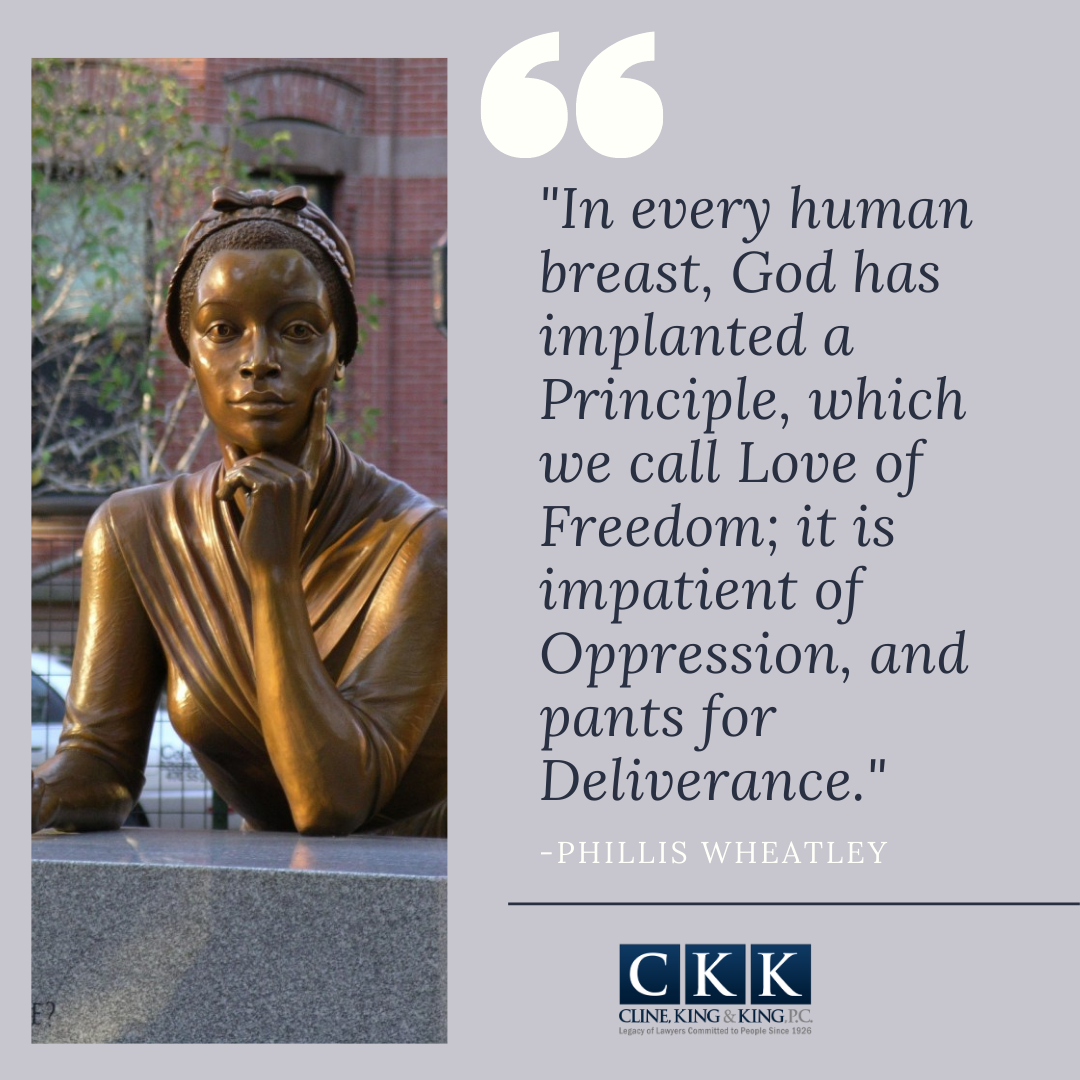

All of us are aware of Amanda Gorman and her impressive poetry presentation at President Biden’s inauguration. Amanda’s remarkable talents certainly belie her young age of only 22 years old. Many of us probably do not recognize the similar talent of a young woman from West Africa who came to America on July 11, 1761 as a slave at only seven years of age.

Her true given name is lost to history as she was sold by slave traders in Boston, Massachusetts. She was given the first name of Phillis, after the name of the ship that had transported her from Africa, and the last name Wheatley, after the family who had purchased her. Phillis quickly learned to read and write, and the Wheatley family encouraged her talent in poetry.

By age 12, Phillis Wheatley was reading Greek and Latin classics. At 14, she wrote her first poem to the University of Cambridge (now known as Harvard University, where Amanda Gorman herself attended). Many colonists did not believe that a Black slave could write so well, and so Phillis was required to defend her authorship of her poetry in court in 1772. She was further scrutinized by a group of Boston luminaries of the time which included the governor and lieutenant governor of Massachusetts, and John Hancock. They concluded Phillis had, in fact, written the poems and signed an attestation, which was included in the preface of her first book of collected works.

In 1773, at the age of 20, Phillis traveled to London, England accompanied by Nathaniel Wheatley to present her poetry. Her first book, Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral, was published on September 1, 1773 and was the first book written by a Black woman in America.

“On Being Brought From Africa to America “

‘Twas mercy brought me from my Pagan land,

Taught my benighted soul to understand

That there’s a God, that there’s a Saviour too:

Once I redemption neither sought nor knew.

Some view our sable race with scornful eye,

“Their colour is a diabolic die.”

Remember, Christians, Negros, black as Cain,

May be refin’d, and join th’ angelic train.

These words were a gentle but powerful challenge to the racist practices and beliefs in America at the time, indicating that while many discriminated based on skin color, “black as Cain” (an allusion to the belief of many Protestant Christians that Cain’s “mark” was a darkening of his skin), she and other persons of color had the same access to redemption and salvation as white Christians and were equal in the eyes of God.

In November 1773 Phillis was emancipated by the Wheatleys. Susanna Wheatley died soon after in the spring of 1774, and John Wheatley passed in 1778. Phillis married a free black man named John Peters and began a challenging and painful chapter of her life.

By 1784 Phillis had lost two of her three children, her husband was imprisoned for debt, and she was forced to work as a scullery maid to provide for her sickly infant son. Her all-too-brief life ended on December 5, 1784 at the young age of 31, with her son passing soon after.

Her contributions to African-American literary history cannot be ignored and her talent should be celebrated and memorialized.