Throughout the month, Cline, King & King has highlighted Black persons throughout history who have contributed greatly to the United States and beyond. CKK concludes our celebration of Black History Month with John Lewis.

John Robert Lewis was born near Troy, Alabama on February 21, 1940, the third of ten children born to Eddie and Willie Mae Lewis, sharecroppers in rural Pike County. As a child, Lewis dreamed of being a preacher and by age five was sharing the Gospel to his family’s chickens on their farm as his congregation. By age six he had only seen two white people in his life as his county was predominately Black, but as he grew older, he experienced racism such as the public library which was for white people only.

Lewis first heard Martin Luther King Jr. on the radio in 1955 and closely followed King’s Montgomery bus boycott of the same year. Two years later Lewis met Rosa Parks, and a year after that met MLK himself. He wrote to MLK about being denied admission to Troy University, and discussed suing the university for discrimination, but was warned by MLK that doing so could endanger his family. Lewis instead continued his education at a small historically Black college in Tennessee, and was later ordained as a Baptist minister.

As a student Lewis began what would be a long and dedicated journey as a civil rights activist. He organized sit-ins at segregated lunch counters, organized bus boycotts, and other nonviolent protests to support voting rights and racial equality. He was arrested and jailed numerous times for his efforts, but held to his philosophy that it was important to engage in “good trouble, necessary trouble,” to achieve much-needed change in the world.

In 1961 Lewis became one of the 13 original “Freedom Riders”, a group of seven Black people and six white people who planned to ride on interstate buses from Washington, D.C. to New Orleans to challenge policies of segregated seating by southern states which violated federal policy. The mission of the rides was to test compliance of two Supreme Court rulings. Boynton v. Virginia declaring segregated bathrooms, waiting rooms, and lunch counters unconstitutional. Morgan v. Virginia declaring unconstitutional segregation on interstate buses and trains. At age 21, he was the first of the Riders to be assaulted while in Rock Hill, South Carolina as he tried to enter a whites-only waiting room where two white men attacked him, injuring his face and kicking him in the ribs.

This was the first of many assaults on the Riders, as they were often beaten by angry mobs and arrested themselves. One particularly volatile assault was in Birmingham, where the Riders were beaten by an unrestrained mob with baseball bats, chains, lead pipes and stones. Although the Riders were the victims, they were again arrested and taken across the border to Tennessee. They were again assaulted in Montgomery where Lewis thought he might actually die and was left lying at the Greyhound bus station unconscious. 48 years after these attacks, Lewis received a televised apology from Elwin Wilson, a white southerner and former Klansman.

On May 29, 1961 Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy petitioned the Interstate Commerce Commission to ban segregation in interstate bus travel. By November 1, 1961 the ICC ordered removal of “Jim Crow” signs from bus stations, waiting rooms and restrooms in bus terminals. The Freedom Riders had obtained success in garnering national attention to demonstrate continued suppression by segregation in the South.

In 1963 Lewis became chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and became one of the “Big Six” leaders organizing the March on Washington for that summer. Lewis had made a name for himself and was respected for his courage and tenacious adherence to the philosophy of reconciliation and nonviolence, even though he had already been arrested 24 times in his pursuits. As the youngest speaker at the March on Washington, Lewis was chosen to speak ahead of the final speaker, MLK himself with his famous “I Have a Dream” speech. Lewis had prepared a response to President Kennedy’s 1963 Civil Rights Bill, denouncing its failure to provide protection for African Americans against police brutality or with the right to vote. It was revised to indicate that the group supported the Civil Rights Bill, but “with great reservations.”

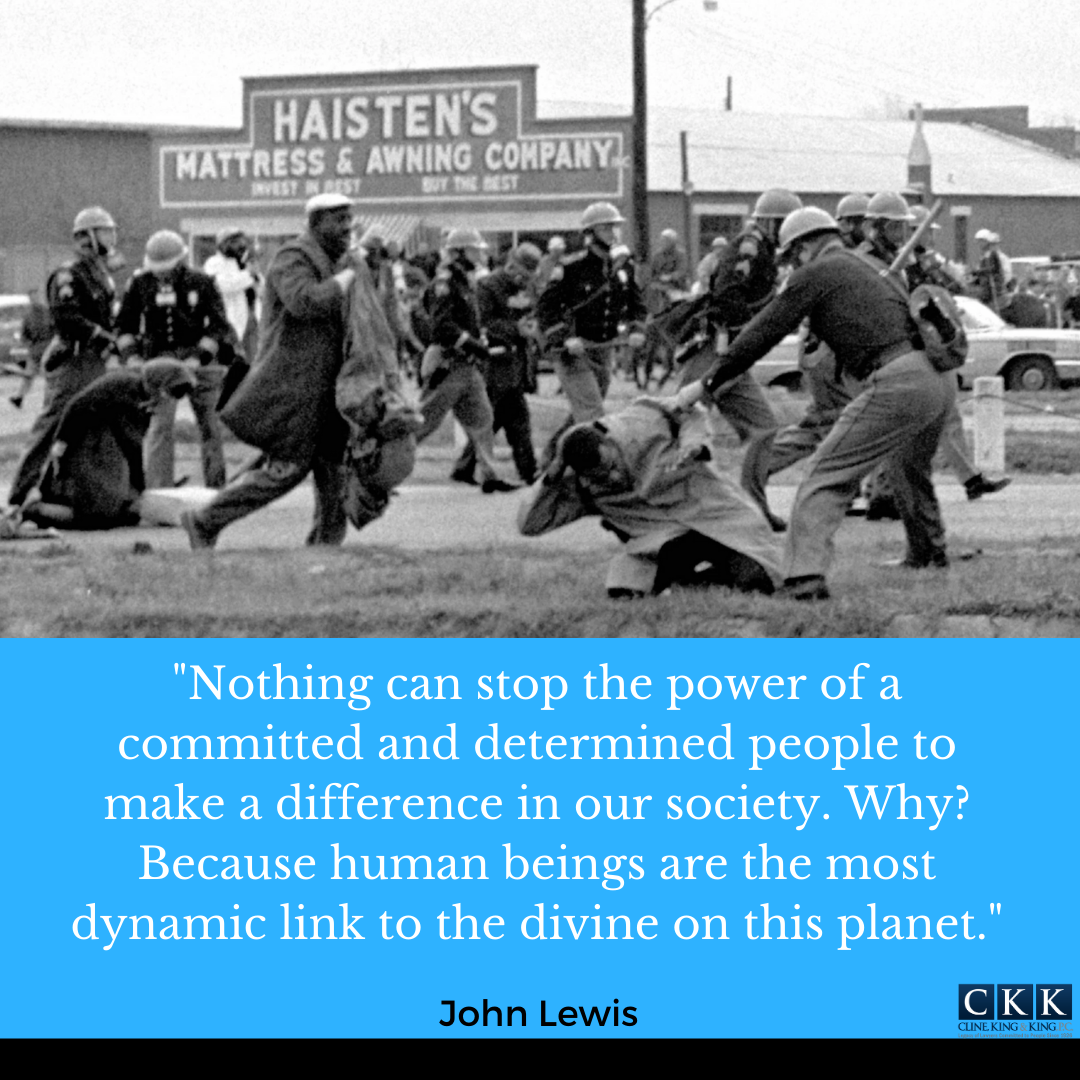

On March 7, 1965 Lewis and fellow activist Hosea Williams led over 600 marchers across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama in what would become known as “Bloody Sunday.” At the end of the bridge, the Alabama State Troopers ordered the marchers to disperse. When they instead stopped to pray, the police discharged tear gas and mounted troopers charged, beating the marchers with nightsticks; Lewis himself suffered a fractured skull and bore scars on his head for the rest of his life.

Lewis was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1986 and was re-elected 16 times. He characterized himself as a strong and adamant liberal, but also fiercely independent. His fight for human rights was not limited to race as he also spoke out in support of LGBTQ rights and national health insurance.

When Barack Obama was elected as the first African-American President of the United States Lewis commented, “If you ask me whether the election…is the fulfillment of Dr. King’s dream, I say, ‘No, it’s just a down payment.’ There’s still too many people 50 years later…that are being left out and left behind.” Lewis was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2011 by President Obama.

In his personal life, Lewis met Lillian Miles at a New Year’s Eve Party and they married in 1968. They had one son, John-Miles Lewis, and Lillian passed on December 31, 2012. On December 29, 2019 he announced he had been diagnosed with stage IV pancreatic cancer. He stated, “I have been in some kind of fight – for freedom, equality, basic human rights – for nearly my entire life. I have never faced a fight quite like the one I have now.” He passed after an eight month battle on July 17, 2020, as the final surviving “Big Six” civil rights icon. His casket was carried in a horse-drawn caisson over the same bridge as “Bloody Sunday,” and he eventually lay in state in the United States Capitol Rotunda on July 27-28, 2020.

In 2013 the United States Supreme Court ruled that the Voting Rights Act of 1965 was unconstitutional requiring Federal approval before local jurisdictions could institute changes to voting procedures such as voter identification laws, drawing new district maps, and restricting early voting. It did so by maintaining key sections of the statute were based upon antiquated data.

In response to the 2013 SCOTUS decision, the House of Representatives passed legislation to update the Voting Advancement Rights Act based upon contemporary data. John Lewis presided over the passage of that bill. However, the Voting Advancement Rights Act stalled in the Senate in 2019. It is anticipated that the Voting Advancement Rights Act will be brought forward in the Senate in 2021. There can be no greater tribute to John Lewis than having a bill passed that protects and affirms the right for which he worked his entire life.

John Lewis once said, “When you see something that is not right, not fair, not just, you have to speak up. You have to say something; you have to do something.“

To further quote Lewis, “If not us, then who? If not now, then when?”Throughout the month, Cline, King and King has highlighted Black persons through history that have contributed greatly to the United States and beyond. CKK concludes our celebration of Black History month with John Lewis.